Hergé at 100

When it comes to the arts, I often think that people divide into two cultural camps. For instance, in the late 1960s, you either liked the Beatles or you were a follower of the Rolling Stones. For me, it was always the allure of the anti-establishment ethos of Londoners Mick and Keith, rather than John and Paul from Liverpool.

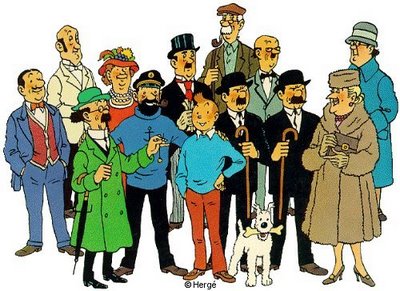

The same sort of split existed between readers of early European comics: You were either a Tintin follower, or you preferred the broad farce of Asterix. I feel in love with Tintin, Snowy, Captain Haddock and the other bizarre characters created in 1929 by writer/illustrator Georges Remi (aka Hergé), who was born in Etterbeek, in Belgium, in 1907. The first of the Tintin works I read was Tintin in Tibet (1958), and this started my love affair with these beautiful comic books. My collection of Tintin books now belongs to my children, but every so often, I dip back into them, just to regain the bittersweet memories of my childhood. These wonderful works, with their weird and surreal perspective on the world in all its wonder, the stories filled with eccentric characters and fanciful storylines, sparked in me a love of both comics and mystery tales. I now consider Hergé to be the father of the graphic novel.

With the centennial of Hergé’s birth coming up in May of this year, Paris’ Centre Georges Pompidou has mounted a special exhibition (on view through February 19) for Tintin lovers, much heralded recently by the London papers. As The Times reports:

There are some readers who might think that things have come to a pretty pass when comic strips, as Hergé’s work might simply be called, get shown at the Pompidou. There was some fuss, you may recall, when an exhibition of the art of Walt Disney, Il était une fois Walt Disney, opened at the Grand Palais in Paris in September ... Never mind the French casting away their usual scorn for American “culture”, what was on display were cartoons. Is this art? We may refer to the Leonardo cartoon, but we don’t mean it that way. We don’t mean talking mice. This kind of thing can only show that the end times, artistically speaking, are nigh.Not to be outdone, London’s Independent on Sunday delivered a special feature titled “Father of Tintin: Hip Hip Hergé!” in which writer Michael Faber (The Crimson Petal and the White, The Apple), among others, pays tribute to the Belgian cartoonist:

So some might say, but it’s hard to get away from the fact that what’s now increasingly called graphic art (though not necessarily by the artists who practise it; they generally prefer to call them comics) has an increasingly respectable profile. For many non-specialist readers, Art Spiegelman’s Maus led the way. A depiction of Spiegelman’s father’s experience of the Holocaust, and the author’s own troubled relationship with his father, this was a memoir like no other. Published as a book in 1986, its second volume won its author a Pulitzer Prize six years later. It was Spiegelman, surely, who led the way for artist-writers such as Marjane Satrapi and Alison Bechdel, whose illustrated memoirs transcend any genres.

But where does that all leave Tintin, quiff-headed boy journalist? He was not, it must be said, Hergé’s first creation, and the Pompidou exhibition covers the artist’s entire career. So fans of Totor (who appeared in the Belgian magazine Le Boy-Scout in the 1920s) will not be disappointed, nor those of Quick and Flupke, two troublemaking boys who also graced the pages of the journal that was the first home of Tintin, Le Petit Vingtième. But the Tintinophiles are probably the most numerous among the Hergélogues, those, such as I, who discovered as children the world of Moulinsart. I read Red Rackham’s Treasure, The Seven Crystal Balls, The Castafiore Emerald first in English and then in French, because it was good practice. Mille milliards de mille sabords! And while I never thought of it as “art”, why should anyone think of anything they enjoy as fitting into any particular category? Recently, it’s true, Tintin has been the subject of an amusingly arcane treatise, Tom McCarthy’s Tintin and the Secret of Literature (Granta), which looks at the books from a literary standpoint and finds comparisons with Austen, James and Dickens. Yes, really. ...

Georges Remi died in 1983; his second wife, Fanny, survives him. When asked recently if her husband was aware of the importance of his work, she said: “I don’t think so. He rarely spoke about his work. He was punctilious and ultra-professional, but he was more of an admirer of the talents of other people. He even collected the works of artists he admired. At one time he was interested in abstract painting and wanted to emulate it. He soon realised that this was not for him. He was very lucid about himself. He had the good sense to stop. He simply concluded: I’m a cartoonist. That’s all.”

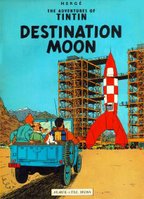

I first read Hergé’s Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon in a state of deep historical and personal confusion. I was nine; the year was 1969. I’d recently emigrated to Australia from my native Holland. As well as leaving my brother behind, I’d been parted from all my familiar comic book characters. Sjors and Sjimmie, Ollie B. Bommel, Agent 327 ... these names meant nothing to my Antipodean playmates. Still, at least there was Kuifje. Even Australians knew Kuifje: the intrepid teenage explorer with his dog Bobbie and his dear friend Kapitein Haddock. Except they didn’t call him Kuifje (a Dutch nickname denoting a duck-tail hairstyle), they called him Tintin.To find more information about the Hergé centennial celebrations, click here. If you’d like to learn more about the Centre Pompidou’s exhibition, visit the center’s Web site, or call 0033-14478 1233. Again, that exhibit runs through February 19, 2007.

My first encounters with The-Adventurer-Formerly-Known-As-Kuifje were those two extraordinary, prophetic spaceflight books that Hergé produced in 1953 and 1954, 15 years before the real moon landing. Except I didn’t know that, either. The books were brand new when my parents bought them for me in 1969. I thought Hergé had just written them to capitalise on the Apollo mission. The Americans struck me as a solemn bunch, but Tintin was sprightly as ever. His moon mission was an action-packed ballet of pratfalls and fisticuffs.

As a child, I never noticed how vacant a personality Tintin was. Unfailingly practical, coolly plucky, and 100 per cent free of vices, he tackled his adventures as though they were bicycle repairs. Hergé understood the narrative shortcomings of his hero, of course, and surrounded him with wonderfully dysfunctional grotesques. On the moon mission, not only did the dipsomaniac Captain Haddock and the dippy Professor Calculus come along, but there were bonus stowaways: the imbecilic detectives Thomson & Thompson, and a dastardly Syldavian spy. Hergé even added a touch of psychedelia, as the stress of space travel triggered a relapse of a syndrome from which the Thom(p)sons periodically suffered -- the sprouting of thick, multicoloured hair growing at several metres per minute, thus needing constant barbering.

For all the knockabout fun in Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon, Hergé constructed them with obsessive care, researching space travel as diligently as he researched the different countries to which he sent Tintin over the decades. But that’s not what makes the books undiminishedly enjoyable even for an adult re-reader. Prose like Enid Blyton’s loses its appeal because the mental pictures we supplied as children vanish when we grow older. The pictures in Hergé’s books continue to exist outside of us. His clear, deft style, perfectly balanced between kinetic cartoon and realistic detail, retains its allure as the years fly by.

READ MORE: “Dalai Lama Honours Tintin and Tutu” (BBC News).

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home